Friday Links

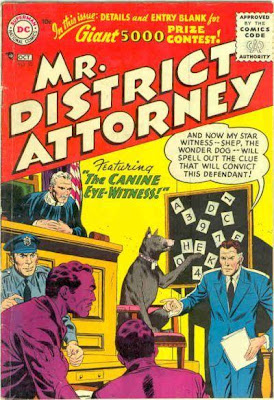

Certainly, in our time, we have seen some trial witnesses fare worse than Shep the Wonder Dog, the canine eyewitness depicted above on the cover of the comic book, Mr. District Attorney #53, published way back in 1956. (Click to enlarge the cover and see it in all its glory!). Shep’s tale must be damaging to the defendant, as the bailiff seems posed to pounce upon the accused, who appears to be rising in response to Shep’s expected testimony. You’d think they would at least wait to see how Shep fared on cross before beginning to worry. Is there an optional completeness objection based upon the fact that Shep’s board does not include all 26 letters, thereby limiting his testimony? Rumor has it that Shep was prepared to give an impermissible lay opinion: Evolution provided the defendant with opposable thumbs but not sufficient wits to outsmart a dog. (For a full summary of this issue, see here.).

The Virginian Pilot in Norfolk, Virginia offers this interesting account of how that state’s courts have dealt with one vexatious litigant (who happens to share the name of the main character on a popular NBC sitcom). Says one jurist: “Within the memory of the incumbent judges of this court, the court has so designated only four people over the past fifteen years [as vexatious litigants]. The petitioner is the most persistent and vexatious of the four.”

Just think. This is what they were saying about law school 72 years ago: “American legal education is blind, inept, factory-ridden, wasteful, defective, and empty . . . [I]t blinds, it stumbles, it conveyor belts, it wastes, it mutilates, and it empties.” Karl Llewellyn, On What Is Wrong With So-Called Legal Education, 35 Colum. L. Rev. 651, 653 (1938). Wow.

The South Carolina Bar has joined Facebook.

Only in a nineteenth century marital property case involving the enhancement value of mules would you find a gem like this: “[T]he erratic mule standeth apart, like patience on a monument, smiling at grief.” Stringfellow v. Sorrells, 18 S.W. 689, 689 (Tex. 1891) (quotations omitted). Back then, we suppose everyone knew without being told that the author of the opinion was referencing Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night.

Speaking of Texas, its state bar is sponsoring a contest of interest. Several writers here at Abnormal Use plan to someday write the great American novel, but we fear that such an enterprise might detract from our billable hours. Perhaps the State Bar of Texas has a solution, though, as it has announced what is surely the first 140 Character Novel Writing contest. Inspired by the popularity of Twitter, the competition is open to all lawyers licensed in any state in the United States. (That’s a lot of lawyers.). Check it out:

Ernest Hemingway reportedly considered his best work to be his most succinct — a six-word novel he came up with to settle a bar bet: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.”

Our contest challenges lawyers to write a short form novel, Twitter-style, in 140 characters or less. All U.S.-licensed attorneys are encouraged to enter.

One grand prize winner will receive an Apple iPad. The grand prize winner and runners-up will receive special recognition at the State Bar of Texas Annual Meeting on June 10, 2010, at a breakfast presentation featuring LexBlog, Inc. CEO and Twitter expert Kevin O’Keefe (@kevinokeefe).

For details, see here. The contest is open until May 1.