1931 was a long time ago, and few who live today can claim to remember it all too well. Just two years after the stock market crash of 1929, 1931 claimed Herbert Hoover as the President of the United States (which that year had 48 states). Movie monsters were the rage; Bela Lugosi starred in Tod Browning’s Dracula film and Boris Karloff did his star turn in Frankenstein. Cab Calloway recorded the classic “Minnie The Moocher” (and he was 49 years from performing it again in 1980’s The Blues Brothers). James Dean was born that year; so were William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy. That December, the first Christmas tree was placed at the construction site that would later become Rockefeller Center. The Lindbergh kidnapping was a year in the future, and the attack on Pearl Harbor – precipitating the country’s entry into World War II – was a full decade away.

It was a far different time culturally, socially, politically. The issue: What did the great minds of 1931 predict the rapidly approaching 2011 would be like?

There is actually an answer to that question.

Way back on September 13, 1931, The New York Times, founded in 1851, decided to celebrate its 80th anniversary by asking a few of the day’s visionaries about their predictions of 2011 – 80 years in their future. Those assembled were big names for 1931: physician and Mayo Clinic co-founder W. J. Mayo, famed industrialist Henry Ford, anatomist and anthropologist Arthur Keith, physicist and Nobel laureate Arthur Compton, chemist Willis R. Whitney, physicist and Nobel laureate Robert Millikan, physicist and chemist Michael Pupin, and sociologist William F. Ogburn. Since these guys all have their own Wikipedia entries so many decades later, they had to have been important for their time, right? Perhaps not a diverse lot, but it was 1931.

Ford, perhaps the most recognizable name to modern readers, set the tone of the project in his own editorial of prognostication:

To make an eighty-year forecast may be an interesting exercise, first of the imagination and then of our sense of humility, but its principal interest will probably be for the people eighty years on, who will measure our estimates against the accomplished fact. No doubt the seeds of 1931 were planted and possibly germinating in 1851, but did anyone forecast the harvest? And likewise the seeds of 2011 are with us now, but who discerns them?

We’re not certain why The Times chose to celebrate an arbitrary 80 years of existence. Whatever the case, the predictions are full of gems, so we encourage you to read the original articles (which, hopefully, The New York Times will unlock from its paywall as 2011 approaches). Today, we are just two weeks shy of 2011, so we must ask, how did some of these men fare in their predictions? Let us do as Ford suspected we would and measure their estimates against accomplished fact (at least as much as a humble products liability blog can do).

Dr. Mayo had this to say:

Contagious and infectious diseases have been largely overcome, and the average length of life of man has increased to fifty-eight years. The great causes of death in middle and later life are diseases of heart, blood vessels and kidneys, diseases of the nervous system, and cancer. The progress that is being made would suggest that within the measure of time for this forecast the average life time of civilized man would be raised to the biblical term of three-score and ten.

Dr. Mayo predicted the average life span in 2011 would be 70. He wasn’t far off. According to this post at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it’s currently 77.9 years.

Interestingly, Keith warned of the coming perils of overspecialization in medicine:

Eighty years ago medicine was divided among three orders of specialists – physicians, surgeons, and midwives. Now there are more than fifty distinct special branches for the treatment of human ailments. It is this aspect of life – its ever growing specialization – which frightens me. Applying this law to The New York Times, I tremble when I think what its readers will find on their doorsteps every Sunday morning.

Any litigator who has ever attempted to secure a medical expert in an obscure field certainly understands the concerns espoused by Keith. All we can say is that Keith would probably not be pleased to see all the various branches of medicine that have arisen in the past eight decades. (But we here at Abnormal Use, as consumers of medicine, are pretty pleased about all the smart folks out there who know lots and lots about important fields and sub-fields of medicine.).

Ford, writing in 1931, just two years after the stock market crash, predicted that we as a nation might focus more on the intangibles of life than the bottom line:

We shall go over our economic machine and redesign it, not for the purpose of making something different than what we have, but to make the present machine do what we have said it could do. After all, the only profit of life is life itself, and I believe that the coming eighty years will see us more successful in passing around the real profit of life. The newest thing in the world is the human being. And the greatest changes are to be looked for in him.

Uh, okay. In these troubling economic times of ours today, we’ll just say, “No comment.”

Millikan observed:

Among the natural sciences it is rather in the field of biology than in physics that I myself look for the big changes in the coming century. Also, the spread of the scientific method, which has been so profoundly significant for physics, to the solution of our social problems is almost certain to come. The enormous possibilities inherent in the extension of that method, especially to governmental problems, has already apparently been grasped by Mr. Hoover as by no man who has heretofore presided over our national destinies, and I anticipate great advances for moving in the directions in which he is now leading.

Certainly, the scientific method has not solved all of our social problems (and Millikan would likely be displeased to learn how history now views President Herbert Hoover.).

Pupin was optimistic that workers would come to share in the profits of that they produced:

The great inventions which laid the foundation of our modern industries and of the resulting industrial civilization were all born during the last eighty years, the life time of The New York Times. This civilization is the greatest material achievement of applied science during this memorable period. Its power for creating wealth was never equaled in human history. But it lacks the wisdom of distributing equitably the wealth which it creates. One can safely prophesy that during the next eighty years this civilization will correct this deficiency by creating an industrial democracy which will guarantee to the worker an equitable share in the work produced by his work.

Er, not quite.

Compton predicted:

With better communication national boundaries will gradually cease to have their present importance. Because of racial differences a world union cannot be expected within eighty years. The best adjustment that we can hope for to this certain change would seem to be the voluntary union of neighboring nations under a centralized government of continental size.

Well, national boundaries are just as important as they were back in 1931. (And in fact, there have been a ton of wars in the past 80 years over just that issue). The United Nations would be formed fourteen years after Compton’s call for a “voluntary union of neighboring nations,” but its efforts and successes over the past 65 years have been, at best, a mixed bag. (Interestingly, Compton also predicted that China, “with its virile manhood and great nature resources,” would take “a more prominent part in world affairs.”).

Our favorite set of predictions, though, comes from Ogburn, who actually went out on a limb and made some bold predictions (some of which were dead on, other of which were not so much):

The population of the United States eighty years hence will be 160,000,000 and either stationary or declining, and will have a larger percentage of old people than there is today. Technological progress, with its exponential law of increase, holds the key to the future. Labor displacement will proceed even to automatic factories. The magic of remote control will be commonplace. Humanity’s most versatile servant will be the electron tube. The communication and transportation inventions will smooth out regional differences and level us in some respects to uniformity. But the heterogeneity of material culture will mean specialists and languages that only specialists can understand. The countryside will be transformed by technology and farmers will be more like city folk. There will be fewer farmers, more wooded land with wild life. Personal property in mechanical conveniences will be greatly extended. Some of these will be needed to prop up the weak who will survive.

Inevitable technological progress and abundant natural resources yield a higher standard of living. Poverty will be eliminated and hunger as a driving force of revolution will not be a danger. Inequality of income and problems of social justice will remain. Crises of life will be met by insurance.

…

The role of government is bound to grow. Technicians and special interest groups will leave only a shell of democracy. The family cannot be destroyed but will be less stable in the early years of married life, divorce being greater than now. The lives of woman will be more like those of men, spent more outside the home. The principle of expediency will be the dominating one in law and ethics.

Not too bad for a man born in 1886 who didn’t live to see 1960. Sure, he was off by about 150 million on the United States population for 2011. Sure, he didn’t predict the microchip or the Internet. Oh, and yeah, poverty hasn’t been eliminated and hunger is still a problem worldwide. But he generally seemed to understand the coming material leisure culture, the rise of big government, and the differences in the family unit in the world eight decades from his prediction.

Oh, and for the record, we here at Abnormal Use do not plan to use this occasion to make predictions about 2091, save for the lone augury that we here will still be toiling away at our desks in an effort to bring you fresh and insightful commentary each business day.

Bibliography

All of the articles listed below are linked and available online, but they’re also all behind The New York Times paywall archive. Unless you have access, all you’ll get is the abstract.

Compton, A.H. “Whole of the earth will be but one great neighborhood; Dr. Compton envisions the great development of our communications,” The New York Times, September 13, 1931.

Ford, Henry “The promise of the future makes the present seem drab; Mr. Ford foresees a better division of the profits to be found in life,” The New York Times, September 13, 1931.

Keith, Sir Arthur. “World we hope for runs away with the pen of the prophet; Sir Arthur Keith doubts if his individualist longings can be realized,” The New York Times, September 13, 1931.

Mayo, W.J. “The average life time of man may rise to the biblical 70; Dr. Mayo says also that a proper use of our leisure will be evolved,” The New York Times, September 13, 1931.

Millikan, Robert A. “Biology rather than physics will bring the big changes; Also, says Dr. Millikan, the scientific method will aid in government,” The New York Times, September 13, 1931.

Ogburn, William F. “The rapidity of social change will be greater than it is now; and hunger, says Dr. Ogburn, will not be a danger as a revolutionary force,” The New York Times, September 13, 1931.

Pupin, Michael. “Our civilization will create a new industrial democracy; it will give the workers a fair share in wealth, says Michael Pupin,” The New York Times, September 13, 1931.

Whitney, W.R. “Better world-wide education will serve our experiments, self-improvement is viewed by Dr. Whitney as the great task set for mankind,” The New York Times, September 13, 1931.

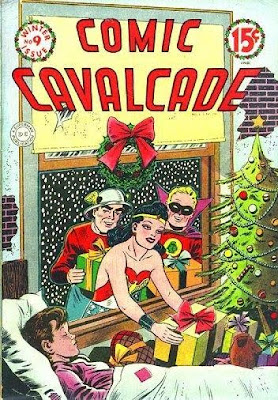

We here at Abnormal Use wish you and your family a very Merry Christmas. We may be cynical, but even we are not immune to those wistful moments of Christmas magic. Were you to send us a request to admit that Christmas is a splendid time of year full of fine sentiment and warm feelings, we could not in good faith deny it. But we’d probably throw in a token objection for vagueness just to preserve our street cred. Above, you’ll find the cover of Comic Cavalcade # 9, published way back in 1945 and featuring, once again, almost ancient versions of The Flash, Wonder Woman, and the Green Lantern. We’re a little distressed that those heroes appear to be breaking and entering a local home and usurping the duties traditionally reserved for Santa.

We here at Abnormal Use wish you and your family a very Merry Christmas. We may be cynical, but even we are not immune to those wistful moments of Christmas magic. Were you to send us a request to admit that Christmas is a splendid time of year full of fine sentiment and warm feelings, we could not in good faith deny it. But we’d probably throw in a token objection for vagueness just to preserve our street cred. Above, you’ll find the cover of Comic Cavalcade # 9, published way back in 1945 and featuring, once again, almost ancient versions of The Flash, Wonder Woman, and the Green Lantern. We’re a little distressed that those heroes appear to be breaking and entering a local home and usurping the duties traditionally reserved for Santa.