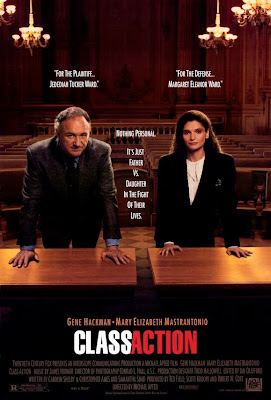

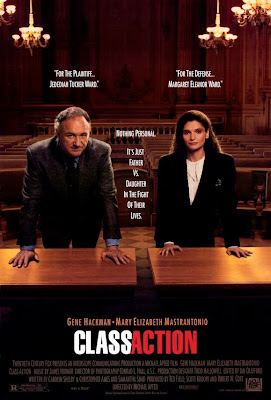

Twenty years ago today, on March 15, 1991, the film Class Action was released to theatres. Directed by Michael Apted, written by Carolyn Shelby, Christopher Ames, and Samantha Shad, and produced by Robert W. Cort, Ted Field, Scott Kroopf (as well as Shelby and Ames), the film chronicles a products liability suit involving an allegedly defective station wagon, which when struck from the rear when the left turn signal is operating, bursts into flames. Essentially, the lawsuit is a fictional version of the famous Ford Pinto litigation. However, the real conflict in the film was familial in nature: Big Law corporate defense attorney Maggie Ward (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio), who represents the automotive company in the suit, is the estranged daughter of Jedediah Tucker Ward (Gene Hackman), the flamboyant plaintiffs’ attorney who brought the suit. Watching the film twenty years later, it’s notable that it made a real attempt to accurately depict the legal process. There are scenes featuring a motion to compel hearing, a discovery document dump, a contentious Plaintiff’s deposition, and ethical dilemmas aplenty for both sides of the bar. Interestingly, the film uses each legal sequence to further and elaborate upon the strained relationship between the father and daughter.

Twenty years ago today, on March 15, 1991, the film Class Action was released to theatres. Directed by Michael Apted, written by Carolyn Shelby, Christopher Ames, and Samantha Shad, and produced by Robert W. Cort, Ted Field, Scott Kroopf (as well as Shelby and Ames), the film chronicles a products liability suit involving an allegedly defective station wagon, which when struck from the rear when the left turn signal is operating, bursts into flames. Essentially, the lawsuit is a fictional version of the famous Ford Pinto litigation. However, the real conflict in the film was familial in nature: Big Law corporate defense attorney Maggie Ward (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio), who represents the automotive company in the suit, is the estranged daughter of Jedediah Tucker Ward (Gene Hackman), the flamboyant plaintiffs’ attorney who brought the suit. Watching the film twenty years later, it’s notable that it made a real attempt to accurately depict the legal process. There are scenes featuring a motion to compel hearing, a discovery document dump, a contentious Plaintiff’s deposition, and ethical dilemmas aplenty for both sides of the bar. Interestingly, the film uses each legal sequence to further and elaborate upon the strained relationship between the father and daughter.

We here at Abnormal Use were fortunate enough to obtain an interview with producer Robert W. Cort and writer-producers Carolyn Shelby and Christopher Ames.

Excerpts of that interview follow below:

[ON REALISTIC DEPICTIONS OF THE LEGAL PROCESS]

SHELBY: It was really a tribute to, well first of all, Michael Apted, the director, [who] came from the documentary world. And he was very committed to doing as honest a depiction of the legal process as you can in a movie. There just has to be some, artistic license to be taken, but he got technical advice, and I was very happy when the movie came out. For years thereafter, various and sundry legal journals would do ratings of movies, and Class Action would always be rated very highly, and the overwhelming reaction was that it did as good a job as was possible to depict the legal process. I was very proud of that because we did work very hard, and we had the luck of a documentarian as our director and the luck of time and the luxury of time to do as good a job as humanly possible when you have to make a story have a true line and you’ve got to focus on characters.

[LOOKING BACK 20 YEARS AT THE FILM]

DEDMAN: Looking back twenty years, what are your thoughts on the film and how it was received as a courtroom or legal drama?

CORT: . . . [O]ne could never get this movie made today . . . Movies in which the ambiguities, the ambivalences, the grays of the world, in which character rules over plot, are almost impossible to get made. The business has changed so much, and I often say that one of the really fortunate things in my career is that I had my career at a time when I could do movies like Class Action, and I have such fond memories and [am] so proud of it. . . . Its really core idea is a relationship between a father and a daughter. It takes the kind of classic, Father of the Bride relationship between a father and a daughter and puts it into, a much darker, much more interesting context and plays out family dynamics as it affects the story.

. . . [W]e began to realize that the father/daughter dynamic was just really a fascinating thing, and then the surrogate son in the part played by Laurence Fishburne became a really interesting character [in conjunction with] the divided loyalties of the daughter. I look back and I’m struck by the ambition of the movie . . . .

SHELBY: . . . When we wrote Class Action with Robert, we went through five years of working [and] did 25 drafts. And that allowed us to go quite a while going in different directions and exploring different ways to do it. You can’t do that now. People make their decisions after one draft or so as to whether or not it’s going to get made.

. . .

CORT: [W]e were incredibly fortunate to be able to develop this in a way outside of the studio. We did develop it completely outside of the studio framework, and we sold it to Fox ,but we were not forced to go through a process. . . . Even in the eighties, even in the nineties, they kind of took the flesh off of anything. So, and I think if you want to look at that, most, many, many, many really wonderful movies were sort of developed outside the studio system.

[CASTING THE FILM; THE NEAR CASTING OF JULIA ROBERTS]

DEDMAN: How did Gene Hackman and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio become involved with the project?

CORT: . . . Gene was always kind of in our mind. We wanted a very powerful character who played against the Henry Fonda of that character . . . We wanted someone who had been toughened and was tough because that’s who those people are; they’re not saints. They’re rough people even if their passions will have been shaded over into obsessiveness. And if you look at a lot of Hackman’s roles, going back to Popeye [Doyle] and The Conversation, you see a character in pursuit of what he believes is right [who] will go to any length and ignore everything else, including, in this particular case, his daughter.

. . . I had seen Mystic Pizza, and there was an enormous amount of heat about this young actress and it was, of course, Julia Roberts. We had given it to a few other major actresses and we’d been passed on . . . The character had a lot of gravitas and huge intelligence and a fair piece of alienation even though she was working very much within the system. . . . Michael Apted and I and Scott and Chris and Carolyn met with Julia, kind of saw what she was like, and she desperately wanted to do the movie. And we really believed in her. I was friendly with the people at Disney and knew that they had not released Pretty Woman yet, but that they were through the roof on the movie. They thought that she was going to be the biggest movie star around and she desperately wanted to do it, we wanted her, Joe Roth, who was the head of Fox, just didn’t believe in her, and he just kept fighting us and fighting us and he said “Well, all right maybe.” And we thought, “Oh my God, we’re going to get her.” And then he called me one day, and he said, “Forget Julia Roberts.” He said, “I have just seen the biggest movie star of her generation.” And he had just come from a screening of James Cameron’s The Abyss, in which Mary Elizabeth starred. Mary Elizabeth had been in, at that time, The Color of Money, in which she was great. She’s a terrific actress, absolutely a terrific actress. We couldn’t see the movie because Cameron wouldn’t show us. We never got to see it. Joe was sure it was going to be titanic. Obviously, it turned out not to be titanic. He said, “You’ve got to go to her, and if she doesn’t do it, all right you can use Julia Roberts.” So, we made the offer, she was represented by a man named Sam Cohn, who is a legendary agent in New York, and he gave it to her, and she delayed, and she hadn’t read it. I kept calling, and I said, “Sam, we need an answer ,”and he said, “Yeah, I’ll get you an answer.” I called Roth, and I said, “Look, we’re just getting jerked around, let us go with Julia.” He said, “All right, I’m calling Sam. If she doesn’t commit to it by noon on Friday, noon L.A. time, 3:00 in the afternoon in New York, go with Julia Roberts.” I absolutely kid you not, at 11:55, the phone rang in my office in L.A. and it was Sam Cohn saying “All right, Mary Elizabeth will do the movie.” So, by five minutes, we missed the part being played by Julia Roberts. And I think that it wasn’t just, in my opinion, the fact that Julia Roberts became this enormous star, and we would have been following Pretty Woman, [adding] incalculable value to that. But I think that Mary Elizabeth is a very dramatic actress, and she always went for the very dramatic and the very hard. And Julia, by nature of who she was and what she brought to it, always had that vulnerable, softer quality. And I think it would have been, opposite Hackman . . . it would have taken the movie, perhaps from a commercial standpoint, to another dimension. And the great story was that she got so mad that she went to see Joe Roth and said, “You didn’t believe in me,” and she and Joe Roth became unbelievably good friends. Basically, I didn’t talk to her again until she did Runaway Bride for us.

[DEPICTING THE CHALLENGES OF WOMEN LAWYERS]

DEDMAN: The Maggie character is an interesting one because she is both a young lawyer who wants to make partner, but also a woman in a profession that is dominated by men ,particularly at that time. How do you think the film addresses those issues, and do you think that’s changed in the last twenty years?

AMES: We talked a lot about this in the development of the script. . . . [W]e hung a lantern on that very issue with one particular piece of dialogue between her and her lover, who was also her boss, where she said “I want to make partner on my own, it’s different for a woman in a firm.” I’m not so sure that’s the case anymore. I hope it’s not the case. But certainly in those days, particularly because she was sexually involved with her boss, there was a tremendous stain that she was trying very, very hard to stay away from.

[DEPICTING THE LAW AND FAMILY STRIFE]

DEDMAN: You mentioned the film does portray not just the actions of lawyers in the courtroom but also how some of what happens in the courtroom bleeds into the family life. How many of Jed’s issues with respect to how he relates to Maggie are the result of him being a lawyer as opposed to him just being who he is as a person?

AMES: Well, I don’t think you can necessarily divorce one from the other. It strikes me with Jed that his was a gigantic ego and that informed everything he did, both in his own family and in court. Jed was the kind of character who believed that he could get away with anything just because of the sheer strength of his character. One of the things that we talked to Robert about from the very first day we started developing this script was that we were going to make him a “people’s lawyer” and her a “corporate lawyer.” We had to give each of them significantly large other dimensions to their lives which is why we made him morally compromised and why we made her somebody who second guessed her own decisions.

CORT: Look at Martin Luther King and his sexual peccadilloes. People of that ego, whatever they’re doing, they’re doing it for the right reasons or they tend to believe they are. There is so much testosterone in those people, so much drive, that they need sort of eat everything in their path. I think he was a hugely compelling character in that movie. I never knew anyone who ever said anything other than he felt real.

AMES: He was patterned on some real people. There was a little of Alan Dershowitz in him. There was a little of Tony Serra in him, too. As a matter of fact, the office that you see Jed in – his “office” was Tony Serra’s office – complete with the ashes of a former drug dealer/client [which] was sitting on the desk.

SHELBY: That was put to death by order of the court. And there was artwork all over from prisoners in prison who were using their served out time to paint art.

AMES: So we did have real models out there. Bill Kunstler was a model for him, also. He probably came closer to Kunstler than anybody else.

[REACTIONS OF LAWYERS TO THE FILM]

DEDMAN: What kind of reactions have you gotten from lawyers over the years about the legal elements of the film?

SHELBY: . . . [W]e used to go to theaters that were showing it, and we would come in, all the theaters got to know us, we would come in the last ten minutes of the movie . . . follow the people out and listen to the comments. And we always gravitated toward the lawyers who would be in great debate as they left about [whether the conduct depicted was] ethical. “Could they do this ?” and it went back and forth, and it was hysterical to listen to. But this was wonderful, because there was such huge debate, and these lawyers were having the time of their lives trying to analyze the movie and mainly coming out very positively.

AMES: Perhaps the highest compliments I ever got about the movie was my daughter called me breathless one day from George Washington University . . . to inform me that the plot of this movie was being taught in one of her classes that day and she about fell out of the chair.

[LEGAL ETHICS AND THE FILM]

DEDMAN: . . . [T]here is sort of a debate about some of the ethical decisions made by the lawyers in the film. What Maggie does at the end is probably something she feels is right but may be something that would get her in trouble with the disciplinary authorities.

AMES: I’ve heard arguments for twenty years on both sides of the issues. There are two issues that people always raise about it. Number one is that and number two is whether a father and daughter really could go up against each other in court, and we were scrupulous in our desire to make this an accurate movie.

SHELBY: We also found it was fun during the process of researching and writing it, particularly towards latter stages. At every stage, we wrote a draft that went to the studio, got a response from the legal department who would tell us do this, do that, this isn’t [accurate], and so we would adapt appropriately. So all the way through the process we were getting notes from attorneys, and ironically, we finally hired . . . a technical adviser two weeks before we were going into production. And he was not an entertainment attorney, he was a products liability attorney, and he said, “Well, [I] really loved the script, but it’s not a class action.” How could this be! We came to realize that “Oh, wow, these lawyers are very specialized in their knowledge level, and all these attorneys that we’ve been talking to have not been in the field that was appropriate.” So we then talked to three different class action attorneys who read it and promptly gave us some notes to truly make it accurately a class action. . . . [B]ut the technical advisor, who was a products liability attorney, kept saying, “No, they’re wrong, it’s not a class action.”

AMES: And I must say in the years since the release, no one has ever suggested it wasn’t a class action.

[DEPICTING THE PLAINTIFF’S DEPOSITION]

DEDMAN: There is a scene where Maggie is deposing the plaintiff who is played by Robert David Hall, and in it, she seems troubled that she has to ask him about past accidents and some pre-existing psychological issues that he has related to automobiles. Why is she troubled about that approach?

SHELBY: That that scene was rewritten to death. Every single day for five years, we rewrote that scene.

AMES: A fair amount of that deposition came to us from David Hall who was a friend of mine prior to the filming and when I got David scenes to do the part and David talked about the two-day deposition that he had had where the attorneys for, I think it was Volkswagen in that case, had grilled him over and over asking him the same questions over and over just slightly rephrased and how agonizing it had been for him. I thought always with Maggie was that there was a bit of her wanting to have her cake and eat it, too. That she wanted to be a powerful corporate lawyer, but she wanted to be a partner, but that she had perhaps too many moral qualms about what you had to do to people. There’s a scene just subsequent to that in a bar where she identifies herself as a professional killer. That’s how she saw herself behaving in there [at the deposition], and frankly, the scene that she played just before that with [the character of] Quinn, the main partner in the firm, who said, “I want him eliminated as a viable witness in this case,” she was not so much deposing him as she was destroying him.

SHELBY: . . . [W]e needed to see her be hard and be the good soldier and do what she needed to do. But we also, as the audience, we needed to have her do it in such a way that we wouldn’t hate her. We just would not hate her for the rest of the movie. And that is a balancing act that’s very difficult to write.

[FILMS ABOUT PRODUCTS LIABILITY]

DEDMAN: [T]here have been a number of films since Class Action was released that address this sort of products liability complex litigation class action context. What is it about those types of lawsuits that make them a good backdrop for films?

CORT: It’s always a greedy, irresponsible, immoral force against people who can’t really defend themselves and somebody standing up to them. That’s been at the heart of movies since Mr. Smith Goes to Washington back in the thirties. There’s been this kind of war in America so to speak between the enormous kind of secret respect we give to people who travel and become famous and rich and powerful and this hatred we have for people who trample our rights and the rights of the defenseless. So, I think thematically this has been a part of our society and hence been a part of movies ever since. You don’t see that much of it in major Hollywood movies any more because I think the sense in Hollywood is that the courtroom drama has been completely taken over by television and they just don’t want to do it. . . . But it’s not a staple of Hollywood film any more because Hollywood film is so dominantly about the created world and fantasy worlds that are aimed at sort of all ages audiences and most importantly are aimed overseas. And one of the problems with doing courtroom drama or doing a class action lawsuit like this is that it doesn’t travel well because the laws of other countries are different, the things that are crimes here and not necessarily crimes abroad . . . . So, I think the foreign or the international demands of the business mitigate against anything other than the guy who kills somebody is wronged kind of thing. So I think class action kinds of stuff is, or products liability are becoming more difficult to make work.

[THE PRESIDENTIAL CONNECTION]

DEDMAN: Two of the actors in your film went on the play Presidents of the United States. Donald Moffat in Clear and Present Danger and Gene Hackman in Absolute Power and Welcome to Mooseport and then Fred Thompson [who played a corporate representative in Class Action] actually ran for President. Is that a coincidence?

CORT: If I’m not mistaken, Donald Moffat also played LBJ in a movie.

DEDMAN: That was before Class Action. Is there a presidential coincidence there?

AMES: I’ll answer that question with a line from a review that I read shortly after the movie came out, where a reviewer was pontificating about the movie and actually liked it, but said “Can it be a coincidence that Maggie’s father’s first name is the same as the first name of the second in command in Citizen Kane?” And I read it and out loud I said, “Yes, it can be.”

[LAWYERS AND QUALITY OF LIFE]

DEDMAN: One thing that is always on the forefront of discussions in lawyer magazines and publications is the quality of life issue and how lawyers who are traditionally workaholics can achieve some type of balance between the work they need to do and their obligations to their family. What do you think that the movie says about those issues in light of the strained the relationship between Jed and Maggie?

AMES: If given his choice, Jed would always be working. Jed is a classic workaholic ,and Maggie has inherited that. I also think that the lack attention that Jed and probably Maggie to paid to their familial relationship growing up was something that was bound to bear fruit later on down the line and also put the mother in the position of being the arbiter between these two.

SHELBY: There’s no question that workaholism has worked a great deal on Maggie and Jed and really, I think, many achievers in our country, I don’t know any great thing to say about it except it’s just reality. And I think it’s worse now for attorneys than ever with the decline in opportunities for employment. I would not want to be an attorney. Of, course being a screenwriter wasn’t that far off.

[DEFENSE FIRM AS GOOD GUY IN A FILM?]

DEDMAN: You mentioned that part of the appeal for some of the movies that have been released over the years depicting these types of lawsuits is the David versus Goliath angle – the powerless taking on powerful interests. Do you ever think there will be a film, or is there a way to tell a story, where the large corporate interest isn’t necessarily the bad guy in the lawsuit?

SHELBY: Well, definitely. Good drama is the gray part where you can be ambivalent about who is the good guy and who is the bad.

CORT: I’m not sure where the story is when Goliath beats David. So I don’t know, I’m not, I don’t quite see that.

AMES: What we have here, Jim, is the perfect differentiation between a producer and a writer.

AMES: I think the writer is saying, “Now, wait a minute, this could be interesting. Let’s make this dog dance.”

DEDMAN: Well, is it just that the stakes are not as high if the big company . . .

CORT: You’re suing them and you falsified your claim to make them look bad, I guess. But I don’t really see that. . . . I don’t know what I’m watching there or what I’m supposed to feel. You know, there’s again, I think “The Good Wife” does a lot of ambivalent stuff.

SHELBY: There’s always a bigger firm that is more corrupt, you know?

AMES: There’s the movie: A firm that thinks of itself as being completely corrupt and then comes up against somebody who’s more corrupt.

CORT: Yeah, but then it’s like a pox on everybody . . . Who cares?

[SHELBY, AMES, AND DEF LEPPARD]

DEDMAN: I have to ask [Chris and Carolyn] about “Hysteria – The Def Leppard Story.” How did you get involved in that and how did you prepare to write that script?

. . .

AMES: [Our agent] said “I have this strange news for you.” She said “I’ve put you up for all kinds of projects which you would have been absolutely perfect for and you haven’t gotten them. As a group, I put you up for this and they jumped through hoops to get you.”

SHELBY: We had done a movie that was a TV movie that had not been made on, was it Marge Schott or was it – we had become kind of pigeon-holed in doing autobiographical stories or real stories about people and doing them in a way that, generally, most of the people were proved despicable but we did them giving them the benefit of doubt and depicting their background so that people could understand how the Marge Schotts of the world could happen and characters like that. And so they had read Marge Schott and they had read a project for Proctor & Gamble and they loved that we were able to take [on a] very complex context. We also did a thing on the Olympics bid in Utah and how it was achieved . . . . And they loved how we were able to take very big concepts and compress them into something with a story like that we could do in an economic amount of time. But we were so wrong on every other level . . . we were just too old and you wouldn’t think of us to write this and I had a classical music background. . . . I think one of the things that they did like about us was that we weren’t huge Def Leppard fans . . . . We were going to ask the hard questions and we were going to do our best to make it a compelling story without making it too syrupy.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio, through her agent, declined a request for an interview. Samantha Shad, one of the writers, also declined our request for an interview.]