Friday Links

- Depicted above is the cover of The Incredible Hulk #153, published way back in 1972. As civil litigators, we can’t say we know in detail all the various rules of criminal procedure which govern the sentencing of defendants. However, surely there must be one that could be invoked to allow the judge to sentence The Incredible Hulk in absentia to prevent the result shown above. The shackles they elected to use didn’t seem to do the trick.

- Jeffrey Kuntz of The Florida Legal Blog asks an interesting question: “Is It Proper To Cite To A Shortened URL in An Appellate Brief?” As Kuntz notes, there is a risk inherent in such citations, as the abbreviated link may itself expire, and if it does, there is no way to ascertain the nature or domain of the original link. Best to use the full URL, we think.

- Oh, boy, do we have a bone to pick with Stephen J. McConnell over at the Drug and Device Law blog. Writing about a series of four related court orders, McConnell strayed into popular culture and opined that “any rock band with four letters in its name will produce wretched music. Okay, we agree about Bush, Devo, Fuel, KISS, and TOTO, but AC/DC?! (There is massive disagreement here in Dechert-ville over ABBA, Rush, and Styx.).” We are aghast and agog. Where to begin? First off, Rush is a fine band as a matter of law. There can be no reasonable disagreement as to that fact (although the closest that one may come to creating a fact issue may well be the band’s 1991 album, Roll The Bones, which includes a pseudo-rap in the title track.). But as to McConnell’s more general statement about bands with four letter names, what about Beck, INXS, Muse, Nico (whose “These Days” is sublime), Pulp, Ween, Love (led by the late, great Arthur Lee), Luna, Lush and MGMT? Blur, Cake, Ride (who would inspire a band called Radiohead), RJD2, and Fear (the immortal Los Angeles punk band)? What about glam legend T. Rex and rap star Jay-Z? Sure, we’re torn about Ratt, Asia, Toto, and Seal, but Devo is sacrosanct. Earlier this year, we here at Abnormal Use were very excited to learn that Devo was to play a gig within 60 miles of our fair city, and we were crestfallen when that show was canceled due to an injury suffered by the guitarist. Alas.

- Funny Or Die has posted a new Jackie Chiles video titled “Jackie Chiles Knows The Internet.” You’ll recall that we here interviewed actor Phil Morris – who plays Chiles in the video and on “Seinfeld” back in the old days – here.

- Elsewhere in online video circles, Jon Stewart of “The Daily Show” has a little bit of fun with the reaction of the Consumer Product Safety Commission to news that Shrek souvenir glasses might contain cadmium. See here for that amusing clip.

- Don’t tell our managing partner, but we here at Abnormal Use may sneak out of the office a bit early today to see the Tron sequel. We were kids when the original came out in the early 1980s. The sequel gives us a chance to revisit that era in our minds and recall a time when we had never heard the terms “billable hours” or “document review.”

New Governmental Regulations Seek to Improve Vehicle Safety

Recently, the federal government proposed new rules aimed at improving rear visibility standards for vehicles. The requirements, which the Transportation Department intends to take effect by the 2014 model year, were created to address concerns about drivers unintentionally backing over children. The Associated Press reports that most car makers will comply by installing rear-mounted video cameras and in-vehicles displays, which the governments estimates will add approximately $200 to the cost of each new vehicle.

Recently, the federal government proposed new rules aimed at improving rear visibility standards for vehicles. The requirements, which the Transportation Department intends to take effect by the 2014 model year, were created to address concerns about drivers unintentionally backing over children. The Associated Press reports that most car makers will comply by installing rear-mounted video cameras and in-vehicles displays, which the governments estimates will add approximately $200 to the cost of each new vehicle.

The Case of the Reconditioned Lawnmower and Implications on Strict Liability

Views of 2011 From 1931

1931 was a long time ago, and few who live today can claim to remember it all too well. Just two years after the stock market crash of 1929, 1931 claimed Herbert Hoover as the President of the United States (which that year had 48 states). Movie monsters were the rage; Bela Lugosi starred in Tod Browning’s Dracula film and Boris Karloff did his star turn in Frankenstein. Cab Calloway recorded the classic “Minnie The Moocher” (and he was 49 years from performing it again in 1980’s The Blues Brothers). James Dean was born that year; so were William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy. That December, the first Christmas tree was placed at the construction site that would later become Rockefeller Center. The Lindbergh kidnapping was a year in the future, and the attack on Pearl Harbor – precipitating the country’s entry into World War II – was a full decade away.

It was a far different time culturally, socially, politically. The issue: What did the great minds of 1931 predict the rapidly approaching 2011 would be like?

There is actually an answer to that question.

Way back on September 13, 1931, The New York Times, founded in 1851, decided to celebrate its 80th anniversary by asking a few of the day’s visionaries about their predictions of 2011 – 80 years in their future. Those assembled were big names for 1931: physician and Mayo Clinic co-founder W. J. Mayo, famed industrialist Henry Ford, anatomist and anthropologist Arthur Keith, physicist and Nobel laureate Arthur Compton, chemist Willis R. Whitney, physicist and Nobel laureate Robert Millikan, physicist and chemist Michael Pupin, and sociologist William F. Ogburn. Since these guys all have their own Wikipedia entries so many decades later, they had to have been important for their time, right? Perhaps not a diverse lot, but it was 1931.

Ford, perhaps the most recognizable name to modern readers, set the tone of the project in his own editorial of prognostication:

To make an eighty-year forecast may be an interesting exercise, first of the imagination and then of our sense of humility, but its principal interest will probably be for the people eighty years on, who will measure our estimates against the accomplished fact. No doubt the seeds of 1931 were planted and possibly germinating in 1851, but did anyone forecast the harvest? And likewise the seeds of 2011 are with us now, but who discerns them?

We’re not certain why The Times chose to celebrate an arbitrary 80 years of existence. Whatever the case, the predictions are full of gems, so we encourage you to read the original articles (which, hopefully, The New York Times will unlock from its paywall as 2011 approaches). Today, we are just two weeks shy of 2011, so we must ask, how did some of these men fare in their predictions? Let us do as Ford suspected we would and measure their estimates against accomplished fact (at least as much as a humble products liability blog can do).

Dr. Mayo had this to say:

Contagious and infectious diseases have been largely overcome, and the average length of life of man has increased to fifty-eight years. The great causes of death in middle and later life are diseases of heart, blood vessels and kidneys, diseases of the nervous system, and cancer. The progress that is being made would suggest that within the measure of time for this forecast the average life time of civilized man would be raised to the biblical term of three-score and ten.

Dr. Mayo predicted the average life span in 2011 would be 70. He wasn’t far off. According to this post at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it’s currently 77.9 years.

Interestingly, Keith warned of the coming perils of overspecialization in medicine:

Eighty years ago medicine was divided among three orders of specialists – physicians, surgeons, and midwives. Now there are more than fifty distinct special branches for the treatment of human ailments. It is this aspect of life – its ever growing specialization – which frightens me. Applying this law to The New York Times, I tremble when I think what its readers will find on their doorsteps every Sunday morning.

Any litigator who has ever attempted to secure a medical expert in an obscure field certainly understands the concerns espoused by Keith. All we can say is that Keith would probably not be pleased to see all the various branches of medicine that have arisen in the past eight decades. (But we here at Abnormal Use, as consumers of medicine, are pretty pleased about all the smart folks out there who know lots and lots about important fields and sub-fields of medicine.).

Ford, writing in 1931, just two years after the stock market crash, predicted that we as a nation might focus more on the intangibles of life than the bottom line:

We shall go over our economic machine and redesign it, not for the purpose of making something different than what we have, but to make the present machine do what we have said it could do. After all, the only profit of life is life itself, and I believe that the coming eighty years will see us more successful in passing around the real profit of life. The newest thing in the world is the human being. And the greatest changes are to be looked for in him.

Uh, okay. In these troubling economic times of ours today, we’ll just say, “No comment.”

Millikan observed:

Among the natural sciences it is rather in the field of biology than in physics that I myself look for the big changes in the coming century. Also, the spread of the scientific method, which has been so profoundly significant for physics, to the solution of our social problems is almost certain to come. The enormous possibilities inherent in the extension of that method, especially to governmental problems, has already apparently been grasped by Mr. Hoover as by no man who has heretofore presided over our national destinies, and I anticipate great advances for moving in the directions in which he is now leading.

Certainly, the scientific method has not solved all of our social problems (and Millikan would likely be displeased to learn how history now views President Herbert Hoover.).

Pupin was optimistic that workers would come to share in the profits of that they produced:

The great inventions which laid the foundation of our modern industries and of the resulting industrial civilization were all born during the last eighty years, the life time of The New York Times. This civilization is the greatest material achievement of applied science during this memorable period. Its power for creating wealth was never equaled in human history. But it lacks the wisdom of distributing equitably the wealth which it creates. One can safely prophesy that during the next eighty years this civilization will correct this deficiency by creating an industrial democracy which will guarantee to the worker an equitable share in the work produced by his work.

Er, not quite.

Compton predicted:

With better communication national boundaries will gradually cease to have their present importance. Because of racial differences a world union cannot be expected within eighty years. The best adjustment that we can hope for to this certain change would seem to be the voluntary union of neighboring nations under a centralized government of continental size.

Well, national boundaries are just as important as they were back in 1931. (And in fact, there have been a ton of wars in the past 80 years over just that issue). The United Nations would be formed fourteen years after Compton’s call for a “voluntary union of neighboring nations,” but its efforts and successes over the past 65 years have been, at best, a mixed bag. (Interestingly, Compton also predicted that China, “with its virile manhood and great nature resources,” would take “a more prominent part in world affairs.”).

Our favorite set of predictions, though, comes from Ogburn, who actually went out on a limb and made some bold predictions (some of which were dead on, other of which were not so much):

The population of the United States eighty years hence will be 160,000,000 and either stationary or declining, and will have a larger percentage of old people than there is today. Technological progress, with its exponential law of increase, holds the key to the future. Labor displacement will proceed even to automatic factories. The magic of remote control will be commonplace. Humanity’s most versatile servant will be the electron tube. The communication and transportation inventions will smooth out regional differences and level us in some respects to uniformity. But the heterogeneity of material culture will mean specialists and languages that only specialists can understand. The countryside will be transformed by technology and farmers will be more like city folk. There will be fewer farmers, more wooded land with wild life. Personal property in mechanical conveniences will be greatly extended. Some of these will be needed to prop up the weak who will survive.

Inevitable technological progress and abundant natural resources yield a higher standard of living. Poverty will be eliminated and hunger as a driving force of revolution will not be a danger. Inequality of income and problems of social justice will remain. Crises of life will be met by insurance.

…

The role of government is bound to grow. Technicians and special interest groups will leave only a shell of democracy. The family cannot be destroyed but will be less stable in the early years of married life, divorce being greater than now. The lives of woman will be more like those of men, spent more outside the home. The principle of expediency will be the dominating one in law and ethics.

Not too bad for a man born in 1886 who didn’t live to see 1960. Sure, he was off by about 150 million on the United States population for 2011. Sure, he didn’t predict the microchip or the Internet. Oh, and yeah, poverty hasn’t been eliminated and hunger is still a problem worldwide. But he generally seemed to understand the coming material leisure culture, the rise of big government, and the differences in the family unit in the world eight decades from his prediction.

Oh, and for the record, we here at Abnormal Use do not plan to use this occasion to make predictions about 2091, save for the lone augury that we here will still be toiling away at our desks in an effort to bring you fresh and insightful commentary each business day.

Bibliography

All of the articles listed below are linked and available online, but they’re also all behind The New York Times paywall archive. Unless you have access, all you’ll get is the abstract.

Compton, A.H. “Whole of the earth will be but one great neighborhood; Dr. Compton envisions the great development of our communications,” The New York Times, September 13, 1931.

Ford, Henry “The promise of the future makes the present seem drab; Mr. Ford foresees a better division of the profits to be found in life,” The New York Times, September 13, 1931.

Keith, Sir Arthur. “World we hope for runs away with the pen of the prophet; Sir Arthur Keith doubts if his individualist longings can be realized,” The New York Times, September 13, 1931.

Mayo, W.J. “The average life time of man may rise to the biblical 70; Dr. Mayo says also that a proper use of our leisure will be evolved,” The New York Times, September 13, 1931.

Millikan, Robert A. “Biology rather than physics will bring the big changes; Also, says Dr. Millikan, the scientific method will aid in government,” The New York Times, September 13, 1931.

Ogburn, William F. “The rapidity of social change will be greater than it is now; and hunger, says Dr. Ogburn, will not be a danger as a revolutionary force,” The New York Times, September 13, 1931.

Pupin, Michael. “Our civilization will create a new industrial democracy; it will give the workers a fair share in wealth, says Michael Pupin,” The New York Times, September 13, 1931.

Whitney, W.R. “Better world-wide education will serve our experiments, self-improvement is viewed by Dr. Whitney as the great task set for mankind,” The New York Times, September 13, 1931.

Abnormal Interviews: Law Professor Jill Wieber Lens

Today, Abnormal Use continues its series, “Abnormal Interviews,” in which this site will conduct brief interviews with law professors, practitioners and other commentators in the field. For the latest installment, we turn to torts professor Jill Wieber Lens of the Baylor Law School in Waco, Texas. The interview, which mostly concerns punitive damages, is as follows:

1. What do you think is the most significant new development in torts or products liability of the last year?

I think one of the most significant developments of the last year was the government’s involvement in creating an alternative to tort law – the BP Oil Spill Fund. The Fund is advertised as a superior alternative — no attorneys taking a portion of the compensation received and the compensation should be paid out faster than in a lawsuit. The Fund may also allow claimants to avoid otherwise troublesome legal arguments like the economic loss doctrine, which if applicable, would preclude BP’s liability in negligence for causing pure economic losses.

At the same time, the BP Fund is very different than the 9/11 Fund. BP is funding it and compensating Kenneth Feinberg for his work. BP benefits directly if claimants apply to the Fund instead of heading to the courtroom. At a minimum, BP saves in legal fees and BP won’t pay any punitive damages within the Fund disbursements. I don’t mean to imply that any of this is necessarily inappropriate, but these are issues that were not present with the 9/11 Fund.

2. What component of punitive damages law do you believe is the least understood by civil litigators? Why?

Between the Supreme Court’s recent decisions in Philip Morris USA v. Williams, 549 U.S. 346 (2007) and Exxon Shipping Co. v. Baker, 128 S. Ct. 2605 (2008), there’s a lot about punitive damages to misunderstand. And it’s not just that litigators are confused; it’s the lower courts, too.

In Exxon, the Court expressed its concern that punitive damages are unpredictable. Numerous lower courts are now integrating the concern for predictability into their constitutional analyses. This is understandable because if the Supreme Court is concerned about predictability, then the lower courts should be concerned also. But Exxon was a common law-based challenge to a punitive damage award. Predictability does not appear to be a constitutional issue. Otherwise, an excessive award would be permissible as long as it was predictably excessive. At the same time, the Supreme Court relied very heavily on its constitutional guideposts — mostly the reprehensibility and ratio between compensatory and punitive damage guideposts — in Exxon, so the guideposts and predictability analyses may not differ all that much. The constitutional relevance of predictability is unknown at this point.

3. Generally, how would you characterize the media coverage of punitive damages issues?

The media coverage of punitive damage issues focuses on the outliers — only the excessive punitive damage awards garner attention. This media coverage, of course, fuels tort reform advocates and has likely contributed to states’ adoption of punitive damage caps or statutes requiring payment of a portion of the award to the state.

It’s also interesting to watch whether the media coverage has influenced the Court. In Exxon, the Court noted that studies undercut the thought of mass runaway awards and show that most punitive damage awards do not greatly exceed the accompanying compensatory damage award. Thus, maybe the Court isn’t so influenced. But after discussing these studies, the Court still suggested reform — pegging punitive damages to the amount of compensatory damages.

4. What do you believe is a defense attorney’s best constitutional argument against the imposition of punitive damages?

The best argument will always depend on the circumstances of the case. If the defendant’s conduct is not that bad, then the degree of reprehensibility guidepost probably provides a strong argument. Still though, the argument is a bit abstract because courts have never really been able to explain the “degree” part of this guidepost. How much more should an award be if the conduct is more reprehensible?

From a litigator’s perspective, the best argument is likely based on the ratio guidepost. It’s relatively easy to compare the amount of compensatory damages to the amount of punitive damages. This is also the same reason that courts have latched onto this guidepost and may explain why the Supreme Court’s ultimate suggestion for reform of punitive damages in Exxon was to peg them to the amount of compensatory damages.

5. What federal or state court opinion has been the biggest surprise for you of late, and why?

I don’t know if I’m surprised by the result of the opinion, but an opinion that interested me lately was an Oregon Supreme Court decision entitled Patton v. Target Corporation, — P.3d —-, 2010 WL 4539445 (Or. Nov. 12, 2010) It limited the effect of Oregon’s statute mandating that 60 percent of any punitive damage award be paid to the State.

After trial, the jury awarded the plaintiff $900,000 in punitive damages. Before judgment was entered, the parties settled for an unknown amount and jointly requested dismissal. The State intervened, claiming it was entitled to 60 percent of the punitive damage verdict. Based on the language of the statute, making the state a “judgment creditor,” the Oregon Supreme Court determined that the State is not entitled to anything until the judgment was actually entered. And the parties settled before the court entered judgment.

Unless the legislature changes the language of the statute, this decision creates a huge incentive for parties to settle before judgment is entered. And even if the legislature changes the language of the statute enabling the State to recover, this will present interesting questions regarding whether the parties are limited in their ability to settle late in the proceedings if punitive damages are sought.

BONUS QUESTION: What do you think is the most interesting depiction of tort litigation in popular culture, and why?

Honestly, I try to avoid any depictions of the law in popular culture. I have difficulty enjoying them while knowing that they’re unrealistic. But honest depictions of tort litigation would not be too interesting. Can you imagine a show about document review? It wasn’t pure tort litigation, but “The Deposition” episode of “The Office” is one of my favorites. When the attorney asks to ask Michael [Scott] another question, and Michael responds, “I’ll allow it,” as if he’s the judge – that was a great episode.

BIOGRAPHY: Jill Wieber Lens joined the Baylor University School of Law faculty in 2010 as Assistant Professor. In 2009, Professor Lens was a Visiting Assistant Professor at the University of Louisville School of Law. Before entering academia, Professor Lens practiced commercial and appellate litigation in St. Louis, Missouri. She teaches Torts and Appellate Procedure. Her current research interests include tort reform generally and punitive damages.

Friday Links

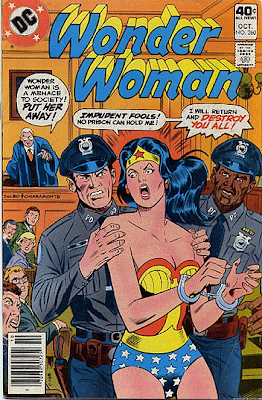

- The cover of Wonder Woman #260, published way back in 1979, depicts the title heroine, in handcuffs, being ushered out of the courtroom by two bailiffs. The judge sternly pronounces: “Wonder Woman is a menace to society! Put Her Away!”, to which she replies, “Impudent Fools! No prison can hold me! I will return and DESTROY YOU ALL!” This is not good courtroom etiquette. (And, in fact, we’re not certain that Wonder Woman’s costume is appropriate courtroom attire.). However, we must admire Wonder Woman’s restraint in respecting the authority of the bailiffs escorting her out of the courtroom in handcuffs while simultaneously vowing to return and erase them from existence.

- Do you dig independent films? Greenville, South Carolina based writer and director Chris White this week released Good Life, a twelve minute movie shot at Ristorante Bergamo, an Italian restaurant just a few short blocks from our law firm’s offices. How about that? White describes the plot as follows: “The Girl’s tenth birthday. A perfectly lovely dinner at a downtown restaurant with her father. Presents, candles, cake. Tonight though, it is she who will take care of him.” There are some tender emotional moments in the film, so we expect that some hard hearted litigators may be confused. But most others will enjoy its the simple joy depicted therein. To watch his new film online, click here.

- Ken Shigley of the Atlanta Injury and Civil Litigation blog shares his remarks from the Bar Admission Ceremony at the Fulton County Courthouse last week. He offers some good tips to the newly minted Georgia lawyers (despite the fact that he’s a Plaintiff’s attorney).

- We believe that any court in the land would find that 1980’s The Empire Strikes Back is the best film of the Star Wars series as a matter of law. No fact issues there, your honor. Thus, we here at Abnormal Use were saddened to learn of the recent death of Irvin Kershner, that austere film’s director. May he rest in peace.

- Professor Mark Osler of the University of St. Thomas Law School (who this site interviewed here back in October) recently blogged about his last day of class for his first semester at that institution, which he joined earlier this year. In so doing, he relates that he found the seating chart for his very first class as a professor at Baylor Law School way back in the fall of 2000. Fun fact: One of the contributors to this blog was in that class.

- We love “Seinfeld,” and we love Twitter. Since Monday, when we published our interview with actor Phil Morris (who played the character “Jackie Chiles” on “Seinfeld,” we’ve learned that Morris is on Twitter. You can find his account here, as well as the one he has set up for the Chiles character here. Finally, Whit Hertford, the writer and actor who is helping Morris with the resurrection of the Chiles character, can be found on Twitter here.

- Last week’s “Question of the Week” at the ABA Journal was “Which law blogger would you most like to meet, and why?” After his interview with Phil Morris was posted this past week, surely everyone would request Kevin Couch from right here at Abnormal Use?

Beware Jury Instructions (or At Least, Pay Attention to Them)

Jury instructions served as the basis for appeal in Kokins v. Teleflex, Inc., 621 F.3d 1290 (10th Cir. 2010) (PDF). This suit arose out of an accident involving a city park ranger, who was thrown from a boat after the boat’s steering cable snapped and sustained a permanent injury to her ankle. She sued the manufacturer of the steering cable, alleging that it was defectively designed and unreasonably dangerous. During discovery, the parties determined and agreed that the reason the cable snapped was because water had somehow entered the core of the cable and caused it to rust. The parties could not agree on how the water got there. The plaintiff alleged that the cable was defectively designed and that a simple fix to the design could have prevented the water from entering into the cable’s core. Teleflex, however, provided evidence at trial that the cable was improperly installed, and had not undergone routine maintenance.

Colorado law provides two different tests. Under the “consumer expectation” test, the jury is instructed to find defectiveness if the plaintiff proves that a product is dangerous “to an extent beyond that which would be contemplated by the ordinary consumer who purchases it.” Under the “risk-benefit” test, the jury is instructed to conclude that a product is unreasonably dangerous if the plaintiff proves that the risks of a challenged design outweigh its benefits. Appellants submitted instructions proposing that the district court instruct the jury under both tests, but the district court gave only the risk-benefit instruction.

Lawsuit Alleging False Advertising and Misrepresented Prices Comes Week Before Black Friday

Think you’re outsmarting the system by avoiding the hoards of Christmas shoppers and choosing instead to order gifts this year online? Perhaps not always the case, according to a complaint recently filed by seven northern California district attorneys against online retail giant Overstock.com, which is headquartered in Salt Lake City. Just as Christmas shopping reaches its peak, the discount retailer has been forced to defend its advertising and pricing practices, both of which have come under fire in the wake of allegations raised by the lawsuit.

Think you’re outsmarting the system by avoiding the hoards of Christmas shoppers and choosing instead to order gifts this year online? Perhaps not always the case, according to a complaint recently filed by seven northern California district attorneys against online retail giant Overstock.com, which is headquartered in Salt Lake City. Just as Christmas shopping reaches its peak, the discount retailer has been forced to defend its advertising and pricing practices, both of which have come under fire in the wake of allegations raised by the lawsuit.