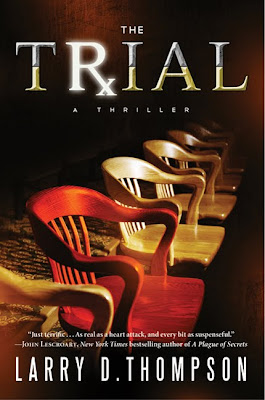

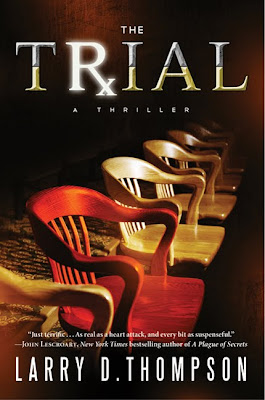

Tomorrow marks the release of Texas attorney Larry D. Thompson’s new novel, The Trial, a legal thriller which chronicles the plight of a small town attorney litigating against a fictional international pharmaceutical company. The book’s protagonist, Lucas Vaughn, is a former Houston-based trial lawyer who migrates to a small Texas town to escape the stress associated with his trial work. His plan appears to be working as his health improves and he is finally able to mend his troubled relationship with his teenage daughter, Samantha. Unfortunately, his new found peace is short-lived. After participating in a clinical trial for a drug manufactured by the fictional drug company Ceventa, Samantha contracts severe drug-induced hepatitis. With her life dwindling away, Vaughn takes the fight to the courtroom. During the litigation, he quickly learns that there are no limits to what Ceventa will do to protect its “revolutionary” new drug. You can see the novel’s “book trailer” (complete with dramatic music) here.

Tomorrow marks the release of Texas attorney Larry D. Thompson’s new novel, The Trial, a legal thriller which chronicles the plight of a small town attorney litigating against a fictional international pharmaceutical company. The book’s protagonist, Lucas Vaughn, is a former Houston-based trial lawyer who migrates to a small Texas town to escape the stress associated with his trial work. His plan appears to be working as his health improves and he is finally able to mend his troubled relationship with his teenage daughter, Samantha. Unfortunately, his new found peace is short-lived. After participating in a clinical trial for a drug manufactured by the fictional drug company Ceventa, Samantha contracts severe drug-induced hepatitis. With her life dwindling away, Vaughn takes the fight to the courtroom. During the litigation, he quickly learns that there are no limits to what Ceventa will do to protect its “revolutionary” new drug. You can see the novel’s “book trailer” (complete with dramatic music) here.

We here at Abnormal Use were fortunate enough to have the opportunity to interview Mr. Thompson about his new book and his inspiration for the tale.

Excerpts of that interview follow below:

[ON PORTRAYING HIMSELF IN THE NOVEL]

FARR: The Trial’s protagonist, Lucas Vaughn is a seasoned UT [University of Texas] law grad, Houston-based trial lawyer. Did you see a little bit of yourself in Lucas?

THOMPSON: Not really. There’s more of me in my first novel, So Help Me God. The protagonist in [So Help Me God] is Todd Duncan. He’s primarily a defense lawyer, so there’s more of me in him. [With Lucas Vaughn] I just wanted a character who had been around the courthouse some. I wanted to put him in a small town, so there’s really none of me. And of course, he was a plaintiff’s lawyer and I had been primarily defense. Although, like any defense lawyer, if a good plaintiff’s case comes along and it’s not against the client, then I’m happy to take the case.

[DEPICTING A LAWYER’S QUALITY OF LIFE]

FARR: Quality of life and the challenge of balancing a successful career with a good home life are serious issues in the legal community. What does the novel say about these issues – particularly in the context of Lucas and his relationship with his daughter, Samantha?

THOMPSON: Well, I think Lucas Vaughn thought he was being a good father. He was faced with having to raise a daughter by himself and I think he thought that “I provided a roof over her head and three meals a day and see her a few hours now and then,” then that’s what a father is supposed to do. He had the rude awakening when he moved her to San Marcos and discovered that his method of fathering really wasn’t all that good. He moved, and he changed his lifestyle. He didn’t change his method in fathering until Samantha flunked out of [Texas] A&M. It was his romantic interest, Sue Ellen, who finally said you need to change it [his parenting style], and he did. That gave him about a year’s worth of a good father/daughter relationship before she took the drug. My old deceased law partner said once that the “law is a jealous mistress.” And that is, in fact, true. No matter what you’re doing, you cannot let it consume you and you’ve got to find time for family. Actually, you’ve got to make time for family. If you don’t, then you end up with problems with your kids and problems with your spouse.

[DIFFICULTY OF REPRESENTING FAMILY]

FARR: In the novel, Lucas represents his daughter as she’s dying of liver failure against the clinical trial physician and Ceventa, the pharmaceutical company that manufactured the clinical drug. How difficult do you think it would be for a lawyer to actually represent a loved one under these circumstances?

THOMPSON: Hugely difficult. I mean, nearly impossible. I wouldn’t recommend it to anybody that they represent a family member. I have some personal experience in that. My brother was a successful lawyer in the eighties. He died way too young. He wrote crime non-fiction. He got sued for libel for a book called Blood and Money in Texas. The first lawsuit was a nothing lawsuit when he lived in Los Angeles. I said, “I’ll handle that for you, and we’ll dispose of it pretty quickly.” Then came two other more serious lawsuits. Suddenly, I’m representing my own brother with three lawsuits, two of which were with very strong plaintiff attorneys. So I had a few sleepless nights as we went through those. We won all three of them primarily because my brother had gotten all his facts right. But to have to represent your daughter when she’s dying is something really that no lawyer in his right mind ought to do.

[ON REALISTIC DEPICTIONS OF THE LEGAL PROCESS]

THOMPSON: I want to make sure that any lawyer that reads this book will think, “Okay, the guy that wrote it really knows something about trials and evidence and what goes on in a lawsuit. It’s not ‘made up.'” From that standpoint, I generally succeed. My first novel had a trial at the end. This one has a trial at the end. The one I’m starting now will end up with a trial. I want lawyers to read it and think, “Okay, this guy really does know something about trying lawsuits.”

[ON MAKING LITIGATION INTERESTING]

FARR: The Trial is about far more than just those proceedings in front of the jury, the trial itself. In the book, you go through the rigors of written discovery, depositions, and pretrial motions. What were the challenges of, not only including a large part of the litigation process in a 300 page novel, but also of making it interesting to the reader?

THOMPSON: That is a challenge. I think the only way it can be done is that you have to – you can’t have talking heads for too long a period of time in any book. The reader is going to get bored when that happens. I think you have to mix in (along with the discovery and the depositions) . . . some scenes that involve a little more conflict, a little more drama, something totally apart from the discovery process itself. I think that’s the only way you can really keep a reader’s attention if you’re talking about discovery and hearings at the courthouse and that kind of thing.

[ISSUES WITH THE LENGTH OF COMPLEX LITIGATION]

FARR: One of the ways you were able to kind of condense the process, I guess, was to have the trial expedited due to the circumstances surrounding Samantha’s health. I believe that Ceventa had 90 days to prepare for trial. In practice, a case of this magnitude can be in litigation for a couple of years before it ever goes to trial, if at all. Do you think that courts should do more to expedite the process – especially in situations like Samantha’s?

THOMPSON: Absolutely. I think that – having been a trial lawyer for a long time, I think we [trial lawyers] waste far too much time in discovery. I really think that we could cut out about three quarters of it and it would not affect the outcome. I’ve actually got a plaintiff bad faith case against a disability carrier that I’m going to go to trial in September, and I’ve elected not to depose anybody from the insurance company. . . . I’ve just decided I’ve got their claim file. I know where I want to go with it. I’ve just decided that I’ve tried enough lawsuits that I’ll cross-examine them at the courthouse for the first time. . . . Of course, the big problem is that you go up against a big insurance company or a big pharmaceutical company or even a big products manufacturer, and they want to wear down the plaintiff’s lawyer and the plaintiff if they can drag it out long enough. I’ve seen it and know it happens. I’ve done it myself. It may not be the best way to achieve justice, but sometimes the money they’re willing to throw at it can just cause one delay after another.

[ON THE DEPICTION OF PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANIES]

FARR: In the novel, Ceventa, the pharmaceutical company, takes some pretty drastic measures – bribery, kidnapping, and murder – to not only have their drug approved by the FDA, but also to protect their interests during the course of the trial itself. Obviously, The Trial is a fiction novel, but were you concerned in any way as a defense attorney about the message that this may convey to readers about large corporations and corporate interests?

THOMPSON: Not really. The reason is because I did do a lot of research. Now, short of murder and kidnapping, well, maybe not even that because where I got interested in this subject was I had a doctor who was on the periphery of the VIOXX litigation and that got me interested in it. There’s a whistle blower named David Graham, who still works for the FDA. He’s a medical doctor and he was interviewed when he blew the whistle on VIOXX and all the problems that it was causing with the heart. He was interviewed by CNN and a question was specifically asked to him, “Because you have come forward and taken this position against Merck [manufacturer of VIOXX], are you in fear for your life?” He [Graham] just said, “Well, I try not to think about that. I am going to do what I think is right.” So far nothing has happened. . . . I’m stretching it a little bit when I tie in kidnapping and murder. As far as bribery , there’s evidence that the FDA has – some people on the FDA have taken bribes. It’s not too big a leap to say that a drug company might commit something like that. But, obviously, that’s fiction.

[ON REPRESENTING THE PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANY]

FARR: If you were standing in Audrey Metcalf’s shoes representing Ceventa, would you have handled the case any differently? Are there any things that you may have done that Audrey did not do during the course of the litigation?

THOMPSON: Good question. I don’t think anybody has posed that question to me. . . . What could she have done differently that might have impacted on the trial itself? I think things got out of her hands. I think she was doing a good job as a defense lawyer. She was throwing up obstacles. She had actually kept the clinical trial results out of evidence with a very innovative theory that the results didn’t make any difference because Samantha was participating in the trial itself. I think that she was on the right track until the results of the clinical trial, including the falsified data, came to light through Ryan Sinclair. I think that once that was done the die was probably cast. But I think if that had not come to light, then I think she was on track to win the case. I don’t think she ever – she, herself, did not know that there was fraud involved in the trial itself. So I really think she did a good job. It was her client who was the one that really torpedoed the case.

[ON WRITING A NOVEL WHILE WORKING AS AN ATTORNEY]

THOMPSON: . . . [J]ust a matter of desire and self discipline. If once you decide you want to write, if you’re still a full time lawyer, then you have to get up a little earlier in the morning and write a couple of hours in the morning and then go to the office. That’s assuming you’re not in trial. If you’re in trial or getting ready for trial, then you’ve got to set the book aside and you’ve got to focus on your trial. . . . I couldn’t do it when I was in your stage in life [young associate] and I was too busy with . . . trial and family and . . . all the other stuff that was part of the world then. That took up all my time and I couldn’t have possibly written a book then. But, when my youngest [child] graduated from college and I said okay, I think I’ll give it a try.

[ON WRITING FROM THE PLAINTIFF’S PERSPECTIVE]

THOMPSON: I think David versus Goliath always has an appeal. So if you’re going to write a David versus big old Goliath story, you want to make David the protagonist. So – actually, I’ll give credit to John Grisham who’s the master of this genre in that he usually has, at least in some of his early novels, . . . some little guy against a big establishment company industry figure or something of that sort. And they succeeded. So I decided, well, if it’s good enough for Grisham, then I think I will. Nobody’s done one on the pharmaceutical companies really, so if I’m going to do one on the pharmaceutical companies, I don’t want to make the drug companies the good guys. I want them to be the bad guys.

[DEFENSE AS THE GOOD GUYS?]

FARR: Do you think it’s possible to tell a story, at least a story that people would actually want to read, where the corporate defendant is the good guy?

THOMPSON: Yes. Actually, I’ll direct you back to my first novel, So Help Me God. It’s not really about a corporate defendant, but I decided that for my first novel I took on a noncontroversial subject. I took on the abortion controversy. I decided I wanted to write a novel that would tell both sides of that without taking sides. I wrote it and I submitted it to a bunch of publishers and agents and, not surprisingly, got rejected by everybody – every single one of them. . . In that I actually presented both sides as evenly as I could. I had two really good, different personalities – lawyers on each side. I wanted to show that the – that lawyers can be professional adversaries, but still not take it personally as we so often see in what we do. . . and that there could be a trial where both sides could have really good lawyers. Both sides could have really good cases to present. Then I thought of a way so that I could end the story without taking a side as far as pro-life or pro-choice, which I did. But that doesn’t quite answer your question about the corporation. Can a corporation be a good guy and a protagonist? I would think probably the best way a corporation could do that is if you made the antagonist the federal government. Most people do not personally align themselves with big corporations. I’ve represented too many in my time, and you have, too. I know you haven’t been practicing very long. Juries usually don’t like big corporations. That’s one of our problems when we defend them.

BIOGRAPHY: Larry D. Thompson is a graduate of the University of Texas School of Law and is a member of Houston’s Lorance & Thompson, PC. While he has tried numerous cases involving products liability, medical malpractice, insurance coverage, and health care throughout his career, in recent years, over seventy percent of his practice has been in the defense of physicians and health care providers.